Season 1, Episodes 6-12

Usually, if I can see a K-drama to the end and really like it, the K-Drama Reports will morph into the Recommended Korean Drama feature, which may retroactively suggest that shows only covered with Reports are not recommended. Looking back, sure, I can’t really recommend My Name, and I never finished Man in the Kitchen, but The Beauty Inside, absolutely, and Inspector Koo is totally worth checking out. I just couldn’t finish the second post about it because of COVID brain fog. I wasn’t able to correct the mistake that the whole show takes place entirely in Tongyeong, and what a great place Tongyeong is. Fool!

Anyway, I’d also recommend Hello, My Twenties! but I can’t yet because we have the rare second season to contend with. So to cap off the first, I want to start with something a little bit different, which is to review the show’s character dynamics. It’s an assertion on my part that they’re the heart of the series, but that may or may not be true. In the meantime, they at least set parameters for my expectations going forward. (Because I love them so much!)

Yoon Jin-myung and Kang Yi-na

Starting with the show’s most intriguing pair, we have the two elder members of Belle Epoque, as well as one of Jin-myung’s few legitimate pairings as a whole. The experience of watching this show about a dorm of 20-year-old women comes with the realization that one of the members is almost never there. Jin-myung is typically out working while the other girls are home after class sharing a meal or throwing a disastrous party. As we know, Jin-myung and Yi-na met each other long before their shared residence, when a group of women was kicking Yi-na’s ass for being a homewrecker. Jin-myung emerged from the convenince store and warded the women off, then told Yi-na to leave, as she was blocking the entrance. People are trying to buy Monster Energy and frozen burritos! Actually, Korean 7-Eleven is awesome.

Yi-na was intrigued by her indifferent savior, who’d become her model for upright citizenry, no matter how often she appeared in the rear-view mirror. I suppose the problem for Yi-na is that Jin-myung is simultaneously a moral paragon and her polar opposite, unconcerned with appearance or material goods. It bothers her, and early on, Yi-na’s voiceover indicates that she wants to like Jin-myung, but just can’t. Their halting interactions are awkward, but they carry a lot of weight. And like in any K-pop group, the sunbaes make for a responsible, paternal duo when the kids are screaming and running around. They could just share a knowing glance amidst the chaos.

Kang Yi-na and Jung Ye-eun

This is my favorite combo, because it’s a time-shifted distillation of a dear K-drama trope: the “enemies to friends.” For me, it’s Hee-do and Yu-rim in Twenty-Five Twenty-One and the friends to enemies to friends of Yeon-do and Soo-ah of Cheer Up! Here, Yi-na and Ye-eun go back and forth. Within the house, they occupy the same ecological niche, being the only eligible bachelorettes and, at the moment, romantically active. They both care about their appearances in a way the other three don’t, so we can maybe say they’re the most “girly.” They like shoes and shopping and makeup. As such, they can relate to each other on at least one level, and one that’s fairly prominent in their lives. They have the easygoing chemistry of “girls who get it,” let’s say, where the other three are almost completely clueless.

You see them at the breakfast table together, even after a bad fight, leading to a complaint that feels right out of Azumanga Daioh: “Can’t you two eat separately?!” The problem is a clash of their respective beliefs and lifestyles. Where Yi-na works as an escort, Ye-eun is a devout Christian. I think what really bothers Ye-eun is how Yi-na comports herself. She’s accepted something unacceptable, and it doesn’t compute. Ultimately, Yi-na is a woman who Ye-eun fundamentally doesn’t understand, and it kind of drives her crazy. But that goes both ways. Ye-eun’s devotion to an abusive boyfriend is something that baffles Yi-na, partly because she’s never felt emotions like that.

I’m certainly disheartened by the prospect of losing the show’s most compelling character in Yi-na. Each of the principals can be boiled down to an archetype, however complicated with time, and Yi-na’s is “badass with a heart of gold.” While as simple as everyone else’s, in practice, it gives the character a lot to do. She’s always gruffly pushing past a housemate and then running to their aid later. Sometimes she combines the two and is gruffly aiding somebody. There’s a basic conflict there, between the preservation of a well-manicured self-image and the inner voice she’s trying to suppress.

There’s that moment when Yi-na returns home in time to witness Ye-eun’s boyfriend Doo-young pull her out of his car and onto the ground, after which she hits Doo-young in the head with her purse. Ye-eun storms into the house and moments later, as a confused Eun-jae stands witness, Yi-na stomps after her and bangs on her door. They get into a screaming match, and Ye-eun slams the door on Yi-na, who then leaves in a huff. This is something that only frustrates Ye-eun further, indeed, that this badass has a heart of gold. How could someone so repellant be, at her core, a good person?

And yet, in the end, it seems that Ye-eun is the moral victor. Yi-na will give up her misbegotten ways to pursue a more normal career, and that’s pretty much how it’s framed. It isn’t “She’s finally chasing her dream,” because her interest in designing fashion comes from her interest in having worn fashion – it’s all she knows. My instinct as an American TV-goer is that the other women should have learned to accept Yi-na’s alternative lifestyle, especially as I got a lot out of those culture clashes, over how difficult and novel Yi-na presented to the rest of the household. I love her outward confidence, this sort of Don Draper-esque self she projects. I prefer when it’s undercut by moments of levity rather than direct thematic deconstruction, like that micro moment when she pushes Ji-won out of the way to get into the bathroom. That slayed me.

Song Ji-won and Jung Ye-eun

These two are probably the friendliest in the house, both in general and with each other. Despite that we discover how Ye-eun really feels about Ji-won – she’s judgmental, which is no surprise – they get along and are both unlucky in love in their own ways. I would venture to guess that part of Ji-won’s appeal to Ye-eun is that she isn’t a threat like Yi-na.

Together, they form a kind of buffer for Eun-jae against the sunbaes, as they’ve allowed themselves to be more openly curious. Jin-myung may peer over her coffee mug every now and again, but both she and Yi-na wouldn’t make themselves vulnerable enough to engage in the affairs of others.

Song Ji-won and Yoo Eun-jae

This relationship was the subject of the previous Report, in which I was disappointed by what I saw as a romantic tease. In 2016? Way too early. And I feel like a K-drama is never gonna surprise us with something like that; it’ll be thoroughly marketed and arrive with netizen fanfare (or scorn, and be buried – there are queer K-dramas out there, and I never hear about them). So the question is: did what happen instead fill that void? By the end of the season, I can’t tell if the show has “forgotten” about the relationship between Ji-won and Eun-jae, because where before the younger valued her unnie’s guidance, later on she’s just talking out loud and Ji-won’s within earshot.

Eun-jae turns out to be the show’s biggest hat trick. We’re introduced to Belle Epoque through her eyes, and she gradually asserts her place over the course of the first episode. That’s the crux of her character, illustrated with all of Eun-jae’s hesitation and timidity. She barely makes eye contact and her sentences trail off. Before reaching the final episodes, I was stunned to learn that the actress Park Hye-su was nominated for Most Popular Actress at the 2017 Baeksang Awards, one of the show’s few nominations. I didn’t want to say, but I didn’t think it was a very good performance. I’d later realize it was simply one I didn’t understand.

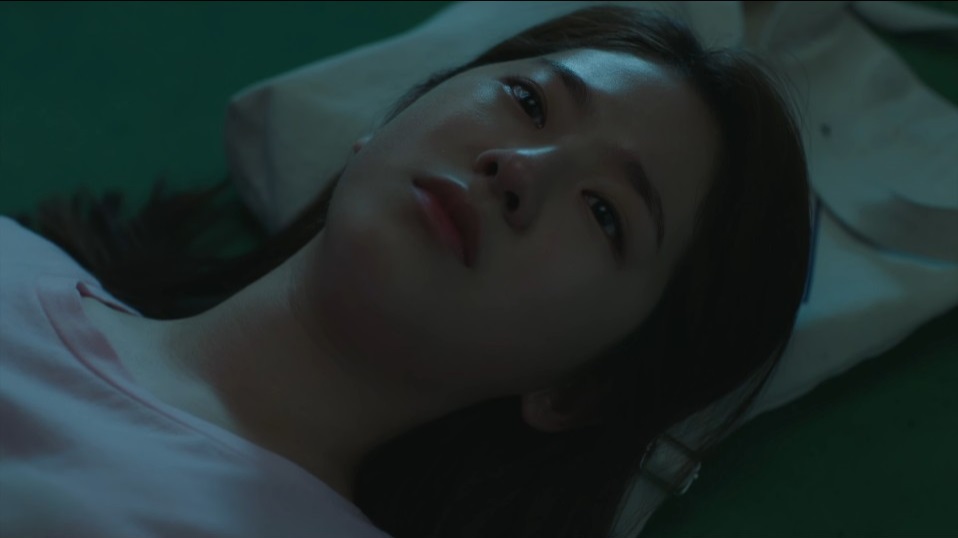

Hello, My Twenties! is the rare show where the proxy character actually becomes more distant and unknown the more we see of her. By the final episode, she’s completely shut down. And then, after her mother jumps behind her at the mistaken sight of a snake, Eun-jae explodes. The silence and the disengagement was really a pent-up swirl of emotions. She’s afraid and angry and sad. She resents her mother for not knowing that she saved her life by killing her father, and she’s dealing with all of this when an insurance adjuster begins poking holes into the mysterious death. This shot of her on the rooftop could’ve come out of Evangelion, to stretch the anime references even further:

While Ji-won isn’t her ultimate savior, Eun-jae’s final arc begins with her. Park Eun-bin is especially funny when she’s playing nervous, as we discover that despite her ghost sighting proving popular with the household, she doesn’t actually believe in ghosts herself. Now she feels like she’s in trouble because everyone else has attributed such meaning to it. So she listens to Eun-jae, and is soon terrified by her story. I love the scene where Eun-jae is cutting an apple and offers a slice to Ji-won, who’s only focused on the knife pointing at her. Eun-jae then goes to her room and eats the slices while staring forward into the void.

The Ending

Like with Yi-na’s late arc, the final two episodes do a lot to simplify the show’s complexities, and I don’t know if it’s a problem or not. I was surprised that a show with a theme as upbeat as Sidney York’s “Dick and Jane” would depict, so frankly, domestic abuse. Doo-young pulling Ye-eun out of the car feels real to me, and it’s evil enough that he didn’t have to become (or be revealed as) an actual “psycho.” I don’t doubt that abusive relationships can escalate to those levels – though I doubt very many end with the bad guy being carted away by the police – but I suppose I saw more value in the earlier scenes, especially when juxtaposed with the girls’ everyday lives. For Ye-eun, being yanked out of a car – in front of her rival Yi-na, no less – is just one of the daily indignities she suffers with a smile. And that was the key: she knows this terrible man is wrong for her, but she likes him. So long as he has dimensions, she can continue to believe in one of the good ones.

The escalation is also a problem because the depiction of male violence was really subtle and really sharp. There’s this ubiquity, a creeping sense of danger, with strange men being spotted outside the house – and it could be any of the men in their lives – and a lot of the abuse happens in private. So now the question is: how ultimately important is realism? Am I asking this show to be 100% representative because representation matters, even putting aside that I can’t say with 100% certainty how representative it is? The counter-argument is twofold: for one, if I want the depiction of violence to be subtle, I already had that. I’m not sure these scenes are entirely canceled out by later, less subtle depictions. And, like, truly not sure. I don’t know.

And two, maybe I need to approach melodrama from a new angle. I can tell you that while contrivance and coincidence feel like narrative shortcuts, this sort of writing is no less difficult than its prestige alternatives. When it turns out that the mother is dying or the piano teacher knew the boyfriend, we’re nonetheless delivered to those moments – we care. The fundamentals are still there, they’ve just taken a heightened expression. And that’s the keyword, because I’m thinking the vector of approach might be something like action scenes in an action movie or musical numbers in a musical. Sometimes critically derided for lacking narrative, these scenes serve different purposes than the meat-and-potatoes “two people in a room arguing” that’s come to define the apex of entertainment. In fact, I tend to think that spectacle better captures what’s possible in film, but of course, the two-hander argument can be spectacle, too.

For me, this is also partly about criticism itself. One of the things I’ve been trying to do lately is fixate less on what isn’t there and focus instead on what is – meet a work of art on its own terms. What is Hello, My Twenties! writer Park Yeon-seon doing when she makes these creative decisions? It’s possible that in hitting the accelerator on Ye-eun’s storyline with her abusive boyfriend, taking things to the absurd extreme (relative to what it had been), she’s speculating. She’s exploring what resilience looks like in that scenario, too. And we see that it’s different. Uncomfortable for me, certainly, but maybe necessary. Emotionally necessary? Necessary for the characters to finally come together? Still, it’s hard for me to say.

One of my favorite moments in a K-drama is in Search: WWW, when Seol Ji-hwan bids farewell to Cha Hyeon outside the cafe. On paper, that’s all that happens. But it’s in the way it’s shot and scored and performed – and even lit. It’s so magical, and so heartbreaking, like time is standing still (with the appropriate amount of slow-motion). This might be the source of my kneejerk against something so big as rescuing Ye-eun from a kidnapping situation. The emotional climax should’ve been earlier, in her goodbye or her passing him on the street that fateful day. Blow up one of those moments with all the tools in the filmmaking toolbelt, right?

As it is, the action climax is more about Eun-jae, whose suicidal tendencies push her toward Doo-young’s knife. He slashes at her and she collapses, leading the other girls – who have pounced on Doo-young – to believe she was cut in the throat or the wrist. She’s taken away in an ambulance as Doo-young is led out of the apartment building in handcuffs. And there’s a note here so curious that it’s even mentioned in one of those weird after-credits interviews: he looks back at Ye-eun, and his gaze softens. The camera has a habit of lingering on the bad men, whether Doo-young or the restaurant manager. It’s how we know that, deep down, Jong-gyu isn’t a bad guy, despite his frenzied attempts to kill Yi-na, first by strangulation and then with a truck. You’d think that would be a deal-breaker.

Not in K-dramas! But more accurately, not in Park Yeon-soo’s K-drama. It might be a mistake to judge her work on a binary calcified by modern American politics, like, does she forgive these men who trespass so severely against women, or is she writing responsibly? Sometimes I think she’s interested in grace, or redemption, but really, I think it comes from an unyielding concern with these women’s lives.

Regardless of how, each of these characters is trying to simply live. Have fun at college, make some money, forget their pasts. They’re not trying to send men to jail or kill daughters. So once again, we see how complicated things can be. The men might want more than they do, and the power imbalance narrows the scope of response. They’re trapped, choosing among wrong answers, like Jin-myung, whispered about for her promotion to the front desk.

I’ve mentioned before how K-dramas can be measured by a “doorbell test,” that whenever a scene between two characters is cut short by a doorbell or a phone ringing, you’re not disappointed because whoever it is will also make for an exciting encounter. I can’t say Hello, My Twenties! always passes this test, because when we cut to a new scene and it’s Jin-myung in the restaurant or, to a lesser extent, Yi-na at the bar, I’m disappointed that they’re not at the house, getting into fights or goofing around. That’s the real dynamite, not – oh, here he comes, Mr. Manager, with a new complaint! What did Jin-myung do wrong this time?!

The show closes on a brief montage of the spaces within Belle Epoque, and once again I’m marveling at how K-dramas get me to care about the most mundane things: cheerleading competitions, web companies, and maybe the best one yet, some girls who live in a dorm. In this one, that’s maybe more the point. It’s interesting, say, how Ye-eun’s story ends on an ellipsis. Her penultimate scene is particularly telling, in which her therapist encourages her to talk about herself for a change, not her housemates, which takes her aback. She’s never really done that before. This is a psychological look at yet another female archetype: the gossip. The one who’s always thinking about other people, even in her diary. She doesn’t make room for herself, even if she urgently needs to.

And so, Hello, My Twenties! is attractive and then satisfying for its insights on the everyday, but remains subject to genre conventions. I want nothing more than to say that the everyday and the conventions are two pieces of a whole, but the show has defied even my suspension of disbelief. If I could give reconciliation one more try – because I don’t ever want to stop talking about this show – maybe it’s a matter of establishing who these people are, and their dynamics, and then applying them to larger-than-life situations. Certainly, this helps their adventures stick in memory, but I’ve never needed help. It’s something else with K-dramas, and it was irresistible here. I’m mourning that it’s over – at least, for now.