Being John Wick

The story of how Bob Odenkirk became an action star begins, of course, with John Wick. The 2014 film was positioned as a comeback for Keanu Reeves, whose star had been tarnished by invisible indies and outright failures like 2008’s The Day the Earth Stood Still remake and an expensive fantasy take on the 47 ronin in 2013. A sleeper hit, John Wick owed its success to Reeves’s persuasion with a global audience – soon to become legendary – and a shift behind the scenes with industry-wide implications. Beginning life as a spec script by relative newcomer Derek Kolstad, “Scorn” was reconfigured as Reeves’s “John Wick movie” by directors Chad Stahelski and David Leitch, two veteran stunt coordinators. These were guys from the trenches of the action genre, with Stahelski having doubled Reeves on The Matrix – as well as being Brandon Lee’s stand-in on The Crow – and directing second-unit on blockbusters like Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Even after the release of John Wick, he and Leitch returned to their day gig for the set pieces on Captain America: Civil War. A nice paycheck, perhaps, but this old way of doing things was coming to an end.

Stahelski gives a great interview. He’s energetic and deeply experienced, and most importantly, interesting. He’s coming in with a unique perspective, as an action director who’s designed action, and even performed it; in Bloodsport III, he squares up against Daniel Bernhardt in the kumite. One of the things he talks about with the original John Wick is how a low budget dictated a Hong Kong approach to the action, with smooth, long takes instead of rapid cuts and a shaking camera, which would’ve required too many setups in a shooting day. It doesn’t take a film scholar to know that this methodology explicitly rejects the stylings of Paul Greengrass (Bourne), Michael Bay (Transformers), and the Taken sequels, then validated by the box office successes of John Wick and especially John Wick: Chapter 2. There was wisdom in something already so logical: action filmmaking driven by action people. And soon enough, an entire Wick series, as well as 2020’s Extraction, directed by fellow stunt coordinator Sam Hargrave, and the ubiquity of Stahelski and Leitch’s company 87Eleven, not to mention the explosion of Wick derivatives: neon colors, long takes, MMA-style action, and a widening lattitude of who can be an action star.

Maybe by necessity, as action was suddenly becoming an “in” genre, like horror, which was also recovering from a doldrums in the 2000s. To accomplish the long takes and in-camera action, you’ll hear Stahelski talk about running the cast through rigorous training and rehearsals and other procedures taken from the set of The Matrix. Altogether, it’s a challenge that A-listers and non-actors alike are warned about in advance, to meet or refuse, like Halle Berry, Charlize Theron, and singer Rina Sawayama, earning plaudits from genre veteran costars for their commitment to the craft. In short, give them a few months of your time, and 87Eleven can turn you into John Wick. We see this democratization trickle out into the derivatives, and in pop culture generally, with movies like Becky (kid action star), Bride Hard (goofy girl action star), Barry (funny guy action star), and of course, things like Old Man (2022), Old Guy (2024), and The Old Man (2022), not that old men were new (Taken, The Expendables). Sure, but what if the old man was also the funny guy? What if he was like Bob Odenkirk, for example, best known for comedy and being decidedly outside the action as Saul Goodman in Breaking Bad?

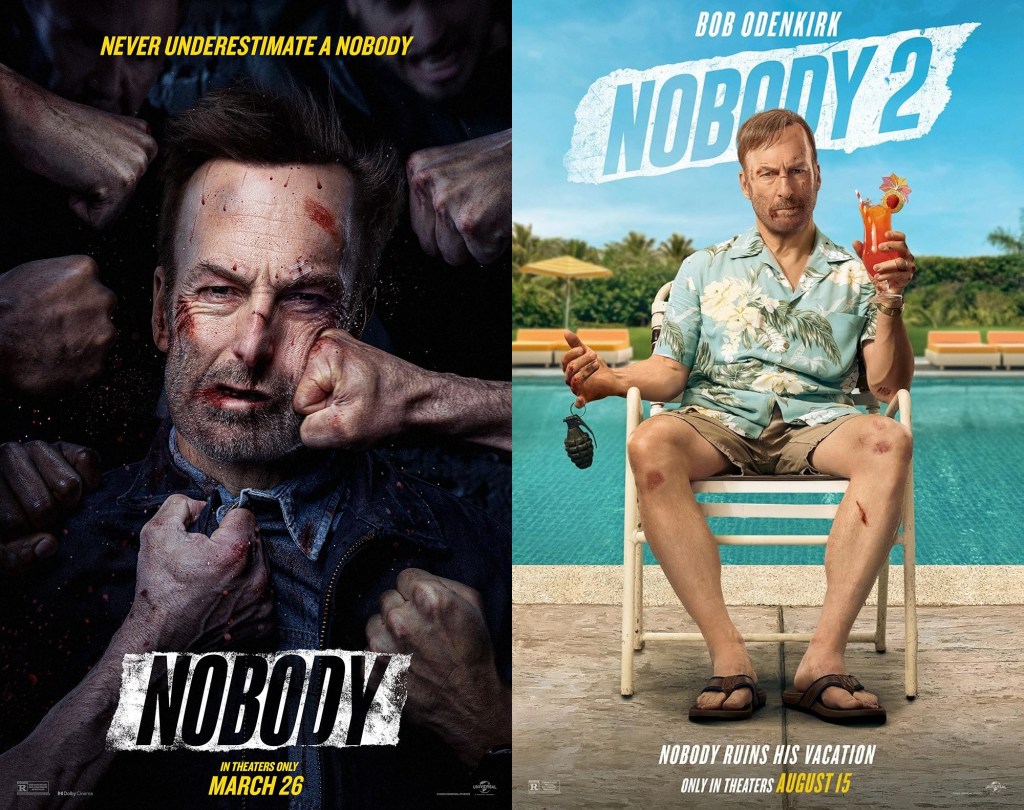

The trailer for 2021’s Nobody is one hell of a tease. Odenkirk plays a middle-aged family man whose house has been broken into. “Mr. Mansell,” a cop says, and then leans in. “Did you even take a swing?” The hoarse answer: “No.” After the Universal logo, we have shots of his character, Hutch Mansell, out jogging, and we hear a different man say, “I wish they’d have picked my place, you know?” Yet a third man inquires, “Why didn’t you take ‘em out?” Hutch punches a brick wall in frustration, and then lies in bed with his wife, the two of them physically apart like they’d returned from a magic show. As this initial sequence draws to a close, he retrieves a revolver from storage and sits on a public bus. These are the themes and images of 1970s revenge. This is Death Wish, in an era when Death Wish was roundly rejected and Joker proved controversial. Necessarily more introspective, then, this movie being teased will be a bracing drama about modern manhood. Oh, but who’s that on the bus? Is that Daniel Bernhardt? By now, this guy’s been killed by Keanu Reeves in John Wick, Charlize Theron in Atomic Blonde, and Bill Hader in Barry (in the future, it’ll be Ana de Armas in Ballerina). This isn’t gonna be limited to six bullets in the chamber.

Even still, our ‘70s revenge story is mostly preserved in the film’s first act. Hutch restrains himself from attacking one of the home invaders – a small woman – with a golf club, giving the other home invader an opening to punch his son in the face before running off. The son, Brady, is reasonably upset about that. His wife, Becca, is just as distant to him as before, though she provides entrée to further emasculation, in the workplace. Hutch is the manager at some sort of construction office owned by his father-in-law; he “married into it,” as Anton Chigurh would say. Also at the office is Hutch’s brother-in-law, a military man who shoves a handgun sideways into his chest. “Protect my sister.” It should be noted that Hutch’s young daughter, Sammy, still loves him and views him as a protector. Even so, we’re about to learn that her pity, however genuinely intended, isn’t necessary. Hutch is no squirrely William H. Macy kind of guy, or a bespectacled Michael Douglas – he’s a highly-trained killer, in the classical Kolstad mold.

Indeed, Nobody was written by Derek Kolstad, who’d ceded creative control of the John Wick series to Stahelski around Chapter 3, and on his own, effects a sort of “Kevin Williamson of action.” His micro-series Die Hart, starring Kevin Hart, plays around with genre conventions to where its working title was “Action Movie,” mirroring Scream’s origins as “Scary Movie.” Nobody, while a self-styled comedy, is surprisingly dour. I want to say I like Bob Odenkirk in the role, but I think I like the idea of Odenkirk in the role more than the performance itself. It’s admirable he’s pulled it off, but Hutch Mansell is so low-key, so put-upon. He’s like Mr. Incredible in the first part of The Incredibles, but even after reclaiming his heroic self, only laments further. Shouldn’t he be shocked by how natural all the violence is? How narcotic? Odenkirk teamed up with Bernhardt to train and develop the action sequences, wherein we locate the spare bits of comedy. In Hutch’s first encounter, on the bus, he’s rusty – and old – and hits his head on a pole. And yet, it’s a brutal, grueling scene, with screaming and exhaustion and increasingly frightened opponents. The colors are muted, there’s no music for half of it, and the bus isn’t even in motion. In violence and especially theme, it’s closer to the subway shooting in Joker than anything in John Wick. Of course, the scene in Joker is meant to be disturbing (I guess?) where this is supposed to be fun.

The climactic sequence is fun. Hutch and his comrades – his father David, played by Christopher Lloyd, and his brother Harry, played by the RZA – set up construction-related traps in the construction office and hunker down for the siege. It’s basically a funhouse of mayhem, with each trap sprung like the payoff to a joke. Harry wields a sniper rifle in close-quarters shooting, which makes me think back to Boardwalk Empire as well as the time when my friend and I got stuck in the video game Conflict: Desert Storm II because we had the wrong guns at the wrong time. I had a sniper rifle during a prison escape level, and while we never made it to exfil, I always thought it would be especially raw to apply “the wrong gun” to an action scenario. Still, for all its technical excellence, a good action scene needs the right narrative frame, for the same reason as WWE wrestlers and sports rivalries. We have to care. By the end of Nobody, I’m confounded by the character Hutch and, by extension, the film itself.

From the perspective of the end of the movie looking back, we have Hutch, ex-badass, who’d left the game to start a family and live an ordinary life, but when that life turns out to be boring – and he’s labeled a coward by no less than four male characters, including his own son – he decides to blow his cover so badly he regrets it later. To be fair, his decisions are portrayed as almost subconscious motion, like he’s being animated by the mythology of man itself – or the rules of the genre – highlighted by the westerns seen on TV in David’s nursing home; a credit to the film language and the cleverness of the script. Like Kevin Hart, old-man Odenkirk is very much in an “action movie,” too. Every step he takes toward the archetype is communicated by shorthand because we know how this story goes. Kolstad is clinking our glass and laughing along with us. But that’s kind of a fucked-up story.

The Action is the Point

Sometimes I wonder – in my study, looking not unlike a Venetian academic at the dawn of psychoanalysis – why John Wick and 87Eleven (or its subsidiary, 87north, which produced Nobody) didn’t do for action what It Follows and Get Out did for horror. We never saw crabby thinkpieces about how there’s no such thing as “elevated action” because “action has always been elevated.” For one thing, movies like Hereditary, The Witch, and The Substance vary in appearance and subject matter, where post-John Wick action movies tend to look and sound the same. Certainly, also, it’s harder to argue that action has really ever been elevated. In America, we don’t have the same legacy as Hong Kong, where the makers of Twilight of the Warriors are throwing back to decades of cinematic tradition itself steeped in Chinese history, folklore, and martial philosophy. Thoughtful filmmaking, with a fair amount of masterpieces. Instead of Lau Kar-leung, Chang Cheh, King Hu, Bruce Lee, Tsui Hark, Sammo Hung, and countless others, we had Arnold and Stallone, typifying the genre with bare-chested vanity only punctured by the pressure-release valve of legitimacy-sinking one-liners (which is part of why Arnold’s got a better catalogue than Stallone, pound-for-pound).

When John Wick: Chapter 4 was rolling out into theaters, I marveled at one of Chad Stahelski’s talking points on the press tour, that the latest sequel boasted fourteen set pieces. I’d never heard any director talk about a movie that way. This is what he was selling: fourteen set pieces. Implicit is that the action is the point. Granted, Stahelski also talked about theme and character, which is the flaw in our theoretical “elevated action” genre, ever elevating the action above all else. In truth, we know which movies our modern action filmmakers are rejecting because they specifically point them out, with Jason Bourne in particular getting a black eye. This is ironic, because the Bourne sequels weren’t exactly action movies anyway. With their emphasis on, like, solving something and advanced technology, I’d always considered them “thrillers.” They were based on books, and had screenwriters like Tony Gilroy and Scott Z. Burns. If they can be boiled down to “chase movies,” they were awfully inefficient. I mean, regardless, they were emblematic of 2000s Hollywood malaise. Not outright terrible, but we never imagined anything better.

Movies like John Wick and Nobody are the inverse, in a very straightforward way. Where The Bourne Supremacy is a story with some action, Nobody is action with some story. Now, the same could be said of a modern classic like The Raid, but that minimal plot was sufficient. It didn’t need to be more complicated, and truthfully, this isn’t about complexity or how many characters or thematic depth, it’s about sincerity. Our “Look, I’m in an action movie” aspect which might seem inescapable with the central project of “Bob Odenkirk, action star,” nevertheless abstracts the action movie now intervening on this family man’s life. The bad guys are referred to by their nation of origin (“the Russians,” “the Brazilians”), there’s some sort of international conspiracy, and rest assured, a big pile of money is gonna go up in flames. Hutch used to be an “auditor,” providing intel to agencies whose charter is intel, but his attempts at clarification are fourth-wall-breakingly cut off when his audiences keep dying. A pretty good gag, but a slick workaround, too. We understand that he was the best of the best, and other details are for outdated, less efficient action movies. Instead, we have our stable of shorthand genre clichés, and it doesn’t feel celebratory or deconstructive or parodic, it feels resigned. “This is just how one of these goes, and” since this is a comedy, “isn’t it all kind of dumb?”

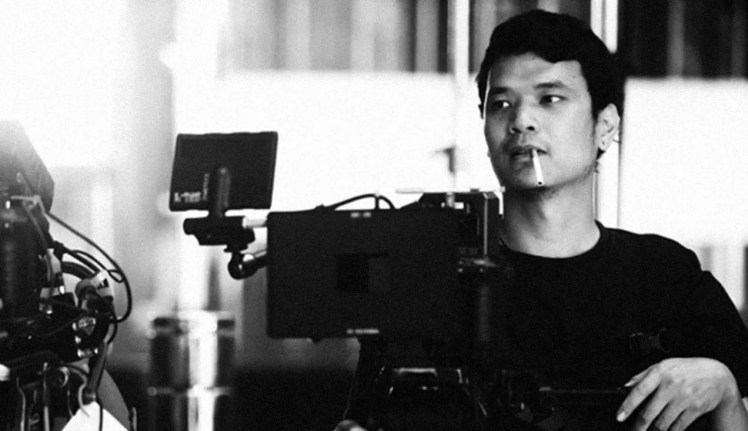

Nobody 2 is directed by Timo Tjahjanto, taking over from Ilya Naishuller. This is, by the way, why the Nobody discussion appears on the Asian movie blog, because the first director was Russian and the second is Indonesian. Tjahjanto is making his American debut here, and it’s an inspired choice. Mostly a horror guy, his flirtation with action has produced wild martial arts epics like last year’s The Shadow Strays and 2018’s The Night Comes for Us – a movie I haven’t been able to stop thinking about. Starring Joe Taslim (Sub-Zero in the new Mortal Kombat) and Iko Uwais (The Raid), The Night Comes for Us impresses with bone-crunching gore – bodies shredded by gunfire, explosions, power tools, and hand-to-hand combat – and an arresting turn by Julie Estelle. Where most filmmakers might make concessions to a woman’s stat bars favoring speed over strength, or keep her out of the violence altogether, Tjahjanto rolls out the red carpet, and Estelle’s Operator kicks the main character’s ass and dispatches an army of bad guys with the sadism of a slasher villain and yet also with exacting precision. My God, I was in love. With who? The Operator, Estelle, Tjahjanto, all of them.

The Night Comes for Us was a success for its distributor Netflix, but apparently not enough to greenlight a sequel, for which a screenplay has been written, bearing the title – wait for it – “Night of the Operator.” For fuck’s sake. In the time since, Julie Estelle seems to have retired from acting (though I wish her nothing but happiness), and of course, Tjahjanto has come to America. Even before Nobody 2 released, he was attached to the remake of Train to Busan and The Beekeeper 2, leaving this hole in my heart indefinitely. Even still, his films are appointment viewing, which is why I finally sat down to watch the original Nobody days before the sequel’s arrival. I’d meant to watch it in 2021, just like I’d meant to watch Extraction and Bullet Train and this year’s Novocaine, not to mention all the great work in the DTV space – Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning, One More Shot, Accident Man. It’s a renaissance! Why am I not celebrating?

I think the John Wick movies keep getting better, but I haven’t been a fan of other contemporary action movies, whether Atomic Blonde or Sisu or either Ballerina. The Equalizer movies are okay, but the less said about The Expendables the better. Unfortunately, Nobody notches as another example, though it still registered surprise. Am I just losing my taste for the genre? I mean, action movies were important to me as a kid because they crossed over so often with science fiction (RoboCop, Terminator 2, The Matrix). It wasn’t much of a leap to Arnold’s non-sci-fi exploits in Commando, True Lies, and even Kindergarten Cop. He was funny and larger-than-life and he could lift people up and drop them over a cliff. God, did I want to see a woman do stuff like that, be that powerful. Eventually, I’d find it in Ghost in the Shell, which like Bourne, is more of a techno-thriller. Its even-more complex storytelling provides the perfect frame for an absolutely brutal heroine. Her blows land with narrative weight, with purpose. Gee whiz, if only they could’ve gotten it right in live-action.

Welcome to the Gun Mr. Show

I think Nobody 2 is the best possible Nobody movie, if the original is more like a proof-of-concept, burdened by a sketch comedy premise stretched too thin. The sequel is more confident and a little more fun. The setting is great, and from what I understand, it was Odenkirk’s idea. The original script drafts called for a trip to somewhere in Europe, but he felt that had been done (to wit: Ballerina). Instead, he wanted Hutch to remain stateside for his big getaway – the kind of vacation spot from his own childhood – in a doomed attempt to reconnect with the family. As widely noted online, the destination is very Griswold, and very much out of time. “Plummerville” boasts the country’s oldest water park – with a somewhat tall slide – a “lodge” somewhere on the premises, and a master bedroom with a woodland-themed hot tub, looking like the Rainforest Cafe. In an age of corporate conglomeration and social media, I cannot imagine millennial parents taking their kids to a non-Disney, non-photogenic place like this. The local cuisine is hot dogs, only one week after their big appearance in Weapons.

About the time when the table saw buzzes on, too near Hutch’s face, I realized that this hadn’t been nor would it likely be a gore-fest. It’s about what you’d expect from a non-Hollywood director tempered by Hollywood, but it’s also appropriate to the story and tone, however confused. I mean, The Night Comes for Us is cringe-inducing, but there’s nothing in Nobody 2 more extreme than the average John Wick. Tjahjanto does, however, draw attention to each sharp, metal object about to be repurposed into a weapon moments before its concussive application. Even without a lot of splatter, there’s plenty of winces as the camera resounds with each impact.

Kolstad returns for scripting duties, along with a cowriter and uncredited contributions by Odenkirk himself. It’s more of the same, with an incomplete thematic arc and winking genre literacy. This time, though, there’s a greater accommodation for the supporting cast, filled out by welcome faces like an against-type Colin Hanks and a very not-against-type Sharon Stone. Unfortunately, there’s also a streak of patronizing simplicity. Early on, Hutch tells his old handler The Barber that he wants to take a vacation. The Barber pauses a beat and says, “Good luck.” A decent laugh, played with the right amount of cool by Colin “Don’t Tell Anyone I Was in Live-Action Blood: The Last Vampire” Salmon, who then gets up to exit the scene. “What do you mean, ‘good luck’?” Hutch asks him. The Barber stops and gives a decidedly post-Kolstad John Wick monologue about how one can never escape their true nature and blah, blah, blah. Come on, guys. Later on, the RZA is saddled with a real clunker, when Hutch asks his dad if he ever worried about his sons, and Harry says something to the effect of “Like you and Brady?” Yeah. Thanks, Bobby D.

Brady is reintroduced with a black eye, as he’s starting to take after his father, a la A History of Violence. In the film’s sometimes heightened reality, it’s difficult to tell just what his family knows of Hutch’s work, which he’s resumed in order to pay off the debt accrued in his encounter with the Russians. Not, you know, because he enjoys it – which he does. And because he feels bad about Brady, he decides to modify his own violence when inevitably he runs into trouble. First, he wreaks havoc on the security staff at Plummerville after Brady gets into a fight with a bully and, crucially, when one of the guards hits Sammy in the back of the head. As before, Sammy is the catalyst. This puts Hutch and his family face-to-face with Sheriff Abel, who turns out to be helping Plummerville’s manager Wyatt smuggle contraband for crazy crime boss Lendina. This is the sort of woman who, after catching a cheater at one of her casinos, has her henchmen, including Bernhardt and a pair of lady assassins, murder all the casino-goers. That sure is crazy!

Abel tells Hutch to leave Plummerville, which is a pretty good deal considering the damage. But the Mansells continue to hang around the park because he’s on vacation, damn it, and had managed to win back an exasperated Becca with a bottle of wine dated to when they first met. Ah, this is the kind of woman that viewers of Breaking Bad would’ve preferred. Abel sends some guys after Hutch, leading to this movie’s version of the bus fight, on a duck boat puttering around in the lake. Hutch does the reluctant Jackie Chan routine, even telling an assailant, “Think of the children!” which returns a confused “What?!” It’s kind of funny, but that’s the extent of the film’s thematic preoccupations. Brady learns nonlethal violence on his own while Hutch and even Becca commit lethal violence to save the day. Regardless, this time I’ve really found the Mansells to be loathsome – and not just because Brady and Sammy refused to share a hotel room as siblings, a request which was granted! I also cannot imagine a millennial who’d choose to remain in a space after being told to leave, so I guess it helps that they’re the only generation not represented here, now that I think about it.

Either loathsome or unreal, because while Becca and Brady are somewhat normal people, there’s the mystical Harry and the goofy David, who wears sunglasses throughout. As we know from the first Nobody, Harry’s supposed to be dead, though we don’t know exactly why. It’s left to the audience as a nod to our genre bona fides, like the Red Circle in John Wick or WUXIA in Chapter 4. “We don’t need an explanation,” we’re saying, except that I never said that. You’re presuming. And look, if you give the RZA a katana, then, yes, you presume correctly. With David, then, it’s more pronounced. A one-joke character in the first film, he’s wandering around the sequel without much purpose. He’s kind of the comic relief (in a comedy), kind of a wisdom-dispenser (to move the plot along), and in the end, he’s another guy who has a gun. He’s just not enough of any one thing to be a readable archetype, never mind a character or a character with an arc. I don’t think it’d be out of step, even with the action pastiche we’re doing, to make David a legitimately affecting character. Somewhere deep in there is a story of fathers and sons, the essential stuff of Hollywood storytelling.

I’m beginning to think that while comedy can augment the horror genre, it undermines action. Admittedly, I liked Hot Fuzz well enough and Jackie Chan is a blind spot for me, but the formula does not work here. The halting stabs at comedy and the genre-literate shorthand, indistinguishable from narrative shortcuts, eat away at the story until it feels like a guy’s been dropped into a fever dream about Russian gangsters and data chips. Once upon a time, action movies were about things. In old kung fu movies, each piece of the choreography was an expression of self-realization or triumph over oppressors or the romantic heroism of a fantastical world. Following John Wick, action movies are about the action itself, which was at first a much-needed, expurgating exercise. It’s been more than ten years.

This frustration I’m feeling likely comes from knowing what I want from the action genre and never, ever getting it, which is another difference with horror. I couldn’t have Mad-Libbed a sequel to 28 Days Later, and part of what I liked about 28 Years Later is the unexpected direction it took. But I’ve been envisioning the action movie of my dreams for decades, and only Tjahjanto has come close, with the Operator in The Night Comes for Us and The Shadow Strays. I mean, 17-year-old Aurora Ribero was fantastic in that movie, but not exactly what I’ve been dreaming about. There’s also the more complex enjoyment of the ‘80s canon, that Commando and The Running Man aren’t “good” in the conventional sense, nor entirely tasteful, so I have to become a different viewer like the toggle of a nictitating membrane and I’m not sure I’m interested in doing that anymore. I don’t honestly think that Nobody and Nobody 2 are bad, but I don’t really like them. This wasn’t meant to be a review of either. It is, for me, a eulogy for the genre.

Instead, we have our stable of shorthand genre clichés, and it doesn’t feel celebratory or deconstructive or parodic, it feels resigned. “This is just how one of these goes, and” since this is a comedy, “isn’t it all kind of dumb?”

Don’tcha fuggin’ hate it when that happens? *Stares in Waititi*

A decent laugh, played with the right amount of cool by Colin “Don’t Tell Anyone I Was in Live-Action Blood: The Last Vampire” Salmon, who then gets up to exit the scene.

🤣🤣🤣🤣

Quintessential Chute essay, loud applause rendered from several states away 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

LikeLiked by 1 person

haha thank you, thank you

Yeah, I don’t think you could pay me to ever sit down and watch Love and Thunder

LikeLiked by 1 person