Directed by Hideaki Anno

Starring Sosuke Ikematsu, Minami Hamabe, Tasuku Emoto

Chances are, if you’ve heard of Shin Kamen Rider, you’re gonna go see it. For my part, I missed Shin Godzilla in theaters and then missed Shin Ultraman. I was determined not to miss Shin Kamen Rider, despite it being my least favorite of the three properties. My experience with Kamen Rider is mostly bafflement. There’s this explosion of light and color, and suddenly, he’s on a motorcycle. Who? I don’t know. The guy who’s running away from the mutants, and he has to stop SHOCKER. Obviously. The difference between Godzilla, Ultraman, and Kamen Rider is a matter of personal taste. I prefer monsters to superheroes, and Kamen Rider is a quintessential Japanese superhero, up there with Astro Boy. Shin Kamen Rider is the 50th anniversary project (adjusted for COVID), and as alluded to, the third in anime maestro Hideaki Anno’s weird revival movies, beginning with the masterpiece Shin Godzilla (technically, it began with Rebuild of Evangelion, but what, are we gonna be here all night?). This movie is a big deal. In fact, it nearly filled the Braintree AMC half to capacity. Put in select theaters for a one-night event by Fathom, the ticket taker at the door looked sideways at my stub. “Uh, that’s theater nine, behind me,” though it was supposed to be theater four. They didn’t even dim the lights for a half hour into the movie. Like I said, big deal.

And despite my going in with little foreknowledge – actually, most of my expectations were taken from promotional cross-talk for the adjacent Kamen Rider Black Sun – I was pickin’ up what Shin Kamen Rider was puttin’ down based on the briefest of experiences with the original series and Kamen Rider Black, television shows from the 1970s and 1980s respectively. Let’s see, our initial protagonist is informed he has superpowers after the fact of their off-screen granting, the professor will immediately die, SHOCKER – remember? – must be stopped. Kamen Rider is the seminal transforming hero, or “henshin,” so while Hongo looks like an ordinary student (in his 30s), he can activate cyborg armor with a distinctive grasshopper theme. Why a grasshopper? Because insects, like humans, are perfect organisms, as Hongo’s new friend Ruriko explains. Also, because it’s reminiscent of a skull, and original Kamen Rider creator Shotaro Ishinomori really wanted to do a skull motif, which was vetoed for obvious reasons (this was a kids’ show).

You’d never know it from Shin Kamen Rider, whose opening motorcycle chase ends in fisticuffs that sprays hot-red blood everywhere. Was this Hideaki Anno’s plan? To bring Kamen Rider to a new, hip generation by making it ultraviolent? I mean, it worked for Shin Godzilla, which was a downright horror movie, but Shin Kamen Rider doesn’t have the same thematic weight or bristling purpose. This is the same kids’ show, where villains talk constantly about their evil plans and how powerful they’re becoming, where the anime-style philosophical conversations are about happiness and despair? Not exactly biting social satire, nor the psychological depths of Anno’s most famous work, Neon Genesis Evangelion. And yet, this is very much a passion project for the legendary filmmaker. Or, you know, “infamous anime guy,” whichever you prefer. Readers of Moyoco Anno’s Insufficient Direction well know that Anno’s most profound love might just be the masked rider. Sure, he plays Ultraman in an early short film, “The Return of Ultraman,” and then again in Shin Ultraman, but he is Kamen Rider.

During the final battle, after the second Kamen Rider has been removed from the action (you got to have a “new Kamen Rider” come in at some point, that’s just part of the mythology), Hongo and the villain gas out, and the choreographed kicks and punches give way to rolling around on the floor, with the camera following from above. I’m amazed that my theater wasn’t laughing, as they were just as given over to the incidents of intentional, deadpan comedy, as well as the excesses of silliness – is this cinema’s least impressive Batman? It reminded me of when I used to make videos with my friends, my own “Return of Ultraman,” experimenting with visual effects in MS Paint and Windows MovieMaker. Sometimes those “fight scenes” were just two guys rolling around on the floor. And it’s here that I think I understand Hideaki Anno’s plan, if only because the experience of being an anime fan is attempting to understand Hideaki Anno.

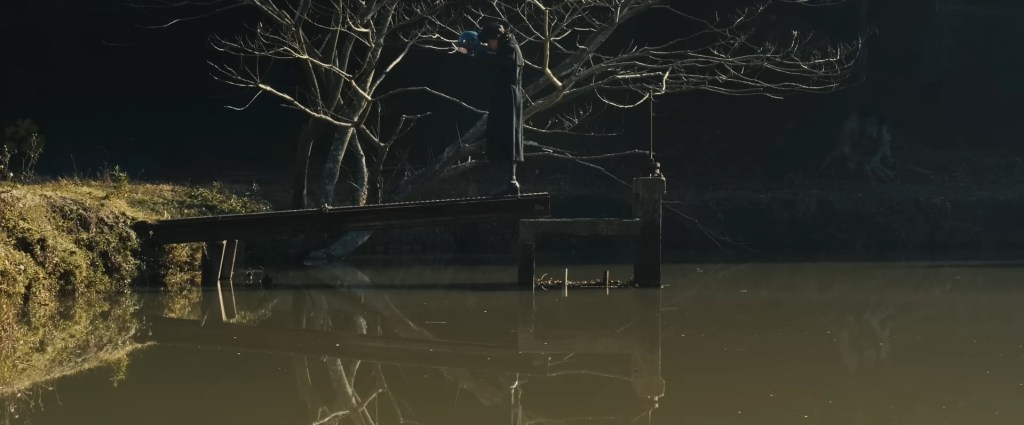

Shin Kamen Rider is like if time stood still in the 1970s. The filmmakers are using all the old tricks, especially trampolines instead of wirework, and only filling in with CG where absolutely necessary (a generous assessment, because the CG is early-2000s Oshii at best). It would be like if Peter Jackson decided to use stop-motion animation for King Kong, or better yet, if Ang Lee shackled himself to Shaw Brothers techniques for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Hongo rides his motorcycle – Cyclone – and as the song goes, he jumps and he kicks. Very funny is the showdown with multiple Kamen Rider clones, where each combatant attacks with the exact same jumping kick. But there’s a strange beating heart to Shin Kamen Rider, where characters realize the folly of their despair or even achieve a moment of happiness before their deaths (and transference to a soul dimension we call the Habitat Realm. It’s… a long story).

When Hongo stands against the sunset, shedding his manly tears, I realize I’ve been watching a story about people born inhuman reclaiming inches of humanity, and it’s surprisingly touching. I may not be as passionate about Kamen Rider as I am, say, Godzilla, but with Shin Kamen Rider, I get why Hideaki Anno is. He sees something greater than what I can see, a garish and grand canvas for both purposely silly sci-fi and convoluted musings on the human condition. He sees a formula that worked in the ‘70s and doesn’t require much of a henshin itself. It needs only the next installment, and buckets of blood. I mean, how metal was it when Kamen Rider No. 2’s face burst out of the mask?